1.104.174

kiadvánnyal nyújtjuk Magyarország legnagyobb antikvár könyv-kínálatát

VISSZA

A TETEJÉRE

JAVASLATOKÉszre-

vételek

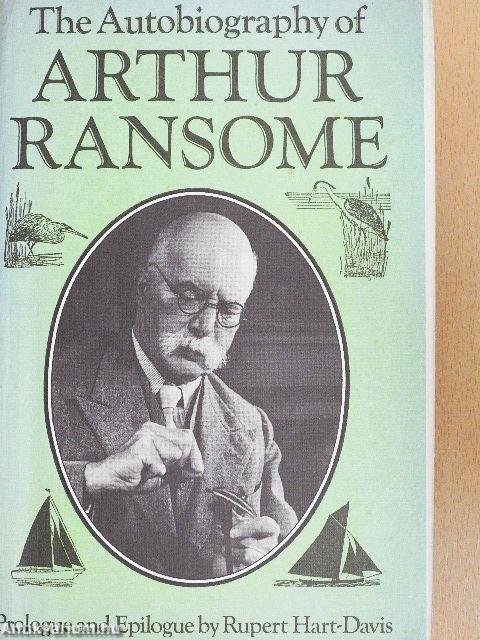

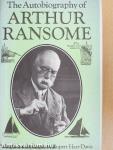

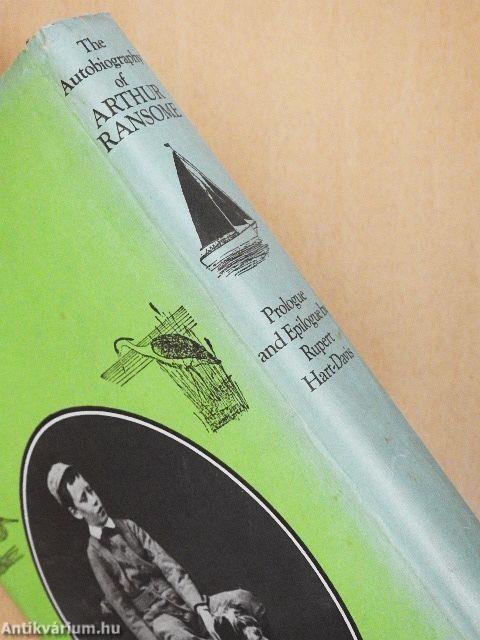

The Autobiography of Arthur Ransome

| Kiadó: | Jonathan Cape |

|---|---|

| Kiadás helye: | London |

| Kiadás éve: | |

| Kötés típusa: | Vászon |

| Oldalszám: | 368 oldal |

| Sorozatcím: | |

| Kötetszám: | |

| Nyelv: | Angol |

| Méret: | 22 cm x 15 cm |

| ISBN: | 0-224-01245-2 |

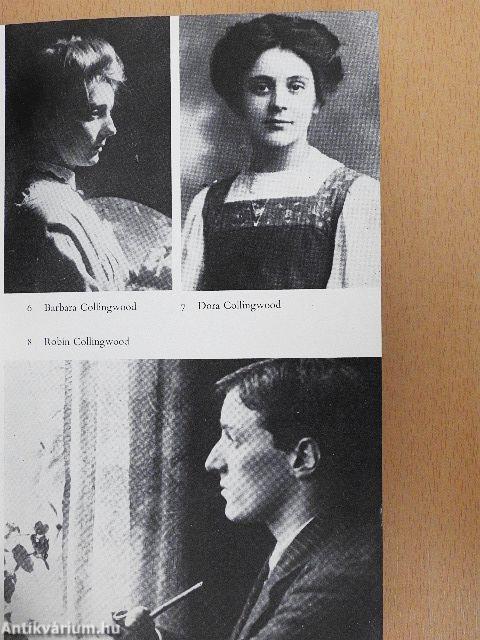

| Megjegyzés: | Fekete-fehér fotókkal. |

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

naponta értesítjük a beérkező friss

kiadványokról

Előszó

TovábbFülszöveg

Arthur Ransome's earliest memory was of being taken, at three-and-a-half, clutching his blue celebration mug, to a Queen Victoria Golden Jubilee tea in an old tithe-barn in Yorkshire, there to be patted on the head by a grey old man who had been a youth of seventeen at the time of the Battle of Waterloo, and had spoken to people who could recall the Highlanders coming into England in 1745. Yet, as he is quick to point out, the memories that are important are less those of 'the touching of the skirts of history' than of quite simple things: drifting snowflakes, the sun like a red-hot penny in a smoky Leeds sky, the dreadful screaming of a wounded hare.

Recalling with astonishing clarity and vividness the smells and sounds, as well as the sights, of schooling at Rugby before the turn of the century, and his daily journey from Clapham by open horse-bus to his first job as a man-of-all-parts in a publisher's office in Leicester Square, Arthur Ransome at once reveals the two sides to... Tovább

Fülszöveg

Arthur Ransome's earliest memory was of being taken, at three-and-a-half, clutching his blue celebration mug, to a Queen Victoria Golden Jubilee tea in an old tithe-barn in Yorkshire, there to be patted on the head by a grey old man who had been a youth of seventeen at the time of the Battle of Waterloo, and had spoken to people who could recall the Highlanders coming into England in 1745. Yet, as he is quick to point out, the memories that are important are less those of 'the touching of the skirts of history' than of quite simple things: drifting snowflakes, the sun like a red-hot penny in a smoky Leeds sky, the dreadful screaming of a wounded hare.

Recalling with astonishing clarity and vividness the smells and sounds, as well as the sights, of schooling at Rugby before the turn of the century, and his daily journey from Clapham by open horse-bus to his first job as a man-of-all-parts in a publisher's office in Leicester Square, Arthur Ransome at once reveals the two sides to his character. Dedicated even in youth to a life of letters, he read everything and soon acquired a passion for language which was to shape the seemingly effortless prose that opened up to children the world he himself loved best — fishing, sailing, camping, bird-watching. Before the First World War he lived an impoverished but gently spirited Bohemian life as a struggling writer in Chelsea; then began his long association with the Manchester Guardian. He reported the Revolution he saw at first hand in Russia in 1917. It was at this time that he met his future wife, Evgenia, then working as Trotsky's secretary. Dogged by recurring stomach ailments in later life, he continued to pursue with zest his love of sailing which always seemed to restore his health, even crossing the Channel against

Continued on back flap

doctor's orders in the last of his many sailing boats in a violent storm at the age of seventy-one.

The enchantment of his autobiography lies above all in his engagingly humorous and clear-sighted view of a long life, rich in experience, conveyed with the directness and enthusiasm of a child's appreciation of simple things. Written over a period of more than a decade in old age, it has remained unpublished during his widow's lifetime. It records many bizarre and unexpected adventures with the same exactitude that magically conjured up a living reality in his famous Swallows and Amazons books and drew from generations of children the abiding question 'Is it real ?'

On the occasion of his eightieth birthday The Times Literary Supplement paid tribute to Arthur Ransome by saying he 'still stands head and shoulders above all living English authors of children's books'. Selecting Swallows and Amazons one of the 99 Best Books for Children, The Sunday Times acclaimed Arthur Ransome 'A master storyteller, sympathetically in touch with real children' who 'has created plots that are entirely plausible and unexpected'. Towards the end of Ransome's full life Ian Serraillier wrote of his 'stature among writers of children's books which no other living author can rival' and Siriol Hugh-Jones promised herself that 'I shall frequently give myself the unspeakable joy of racing through them again, gazing in awe at those magical, flat, laconic pencil drawings'.

Vissza

Témakörök

- Irodalomtörténet > Írókról, költőkről

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Szépirodalom > Regény, novella, elbeszélés

- Idegennyelv > Idegennyelvű könyvek > Angol > Irodalomtörténet

- Irodalomtörténet > Világirodalom > Európai irodalom > Angol

- Irodalomtörténet > Irodalomtudomány > Korszakok > 20. századi

- Szépirodalom > Regény, novella, elbeszélés > Az író származása szerint > Európa > Nagy-Britannia

- Szépirodalom > Regény, novella, elbeszélés > Tartalom szerint > Életrajzi regények > Önéletrajzok, naplók, memoárok